70.) THE MAN WHO WASN'T THERE / A SERIOUS MAN (dir. Coen Brothers)

this might seem like cheating, but i feel as if A Serious Man shed a tremendous amount of light upon the coen bros’ previous work, finally elucidating their proclivities as the framework of true auteurs. the coen bros. have oft been accused of indifferently toying with their characters as a particularly malicious cat might with a ball of yarn or a dead mouse, and while many of have understood that the centrifugal force of their protagonists’ plights is simply the means by which they best tell a story, a Serious Man (when compounded with the memory of The Man Who Wasn’t There) exposed the tactic as the backbone of their entire filmmography. the hero in both of these films is a man who, for worse or for worse, allows life to happen to him without ever bothering to intercede. it feels like the spiteful work of the cosmos, and that lack of control is beautifully communicated by the tug of the camera… compositions that shackle their figures into certain patterns of movement or otherwise prevent them from moving freely about the frame. over the course of both of these films, the hero comes into his own and flirts with the idea of taking action for perhaps the first time in his life, only to discover that the dialectic between control and the (sometimes literal) forces of nature isn’t quite as navigable as they’d hoped. it’s a damned if you do damned if you don’t scenario… action is seen as a moral imperative, but the arrogance to think all the angles are covered is a death sentence. SPOILER ALERT - that both films end in their protagonists sentenced to death (by law or by cancer) is simply a matter of narrative immediacy… death comes to us all, but by the end of every coen brothers film the protagonist, they’ve abandoned the futile attempts to do the impossible and figure it all out (“who cares about the goy!?”) and resigned themselves to either post-priori satisfaction or cinema’s most smirking tornado, en route to making irrelevance out of everything.

this is all quite reductive for the sake of brevity, and discounts the milieus in which the coens elected to set these particular stories, as well as the luminous sense of humor they can’t help but include in even their most somber films. both of these movies are beautiful and seriously enjoyable, and more than a little liberating.

The rest after the jump!

69.) SYMPATHY FOR MR. VENGEANCE (dir. Park Chan-Wook)

my thoughts on this one here

68.) THE FIVE OBSTRUCTIONS (dir. Lars Von Trier and Jorgen Leth)

the cinematic response to the eternal question of “how many ways can you skin a cat?,” this - like most von trier projects - is only as sadistic as it is revelatory. the Great Dane demands his mentor Jorgen Leth to remake an absurdist short film from early in the latter’s career… a short film called “the perfect man” in which a man dances before a white backdrop over a laconic and godly voiceover. more specifically, von trier requires Leth to remake The Perfect Man 5 times, each time constrained by a different “obstruction” - some terrific hindrance to the filmmaking process that von trier hopes will force Leth to better explore his art via the agonizing hindrances he must circumvent. the first obstruction is that the film must be re-made in cuba and with no shot lasting for longer than 12 frames, the 2nd is that Leth must make the film in the worst place on earth but not actually show that place, the 4th that it must be animated, etc… the playful tit-for-tat between the two filmmakers is half the fun, but the results of the obstructed remakes reveal both the capacity of the artist and the capacity of cinema itself, along with detailing the relationship between cinema and the natural world. for that 2nd obstruction, Leth is forced to shoot a scene in which the perfect man (played by himself) dines on a massive feast in the middle of India’s most malnourished slum. dozens of curious and ostensibly hungry children gather behind the somewhat translucent screen in front of which Leth eats (with difficulty). the scene contains obvious multitudes, not the least of which is the moment in which von trier’s storied sadism has actually crossed from the controlled realm of fiction into the real world, a moment which - among many other things - allows the viewer to approach his fiction works with an eye for a deeper strata of meaning.

67.) 28 DAYS LATER (dir. Danny Boyle)

i’ll take a lot of heat for this, but i feel this is both boyle’s best film as well as the best zombie movie ever made. while it certainly stands on the shoulders of giants, alex garland’s script is as rich a ride as they come. taut, perfectly modulated, and impressively ambitious, the heart-warming story of the man-made “rage virus” that ravages england, leaving in its wake an army of cinema’s most aggrieved undead is told in 3 easily defined acts that cohere into an indelible whole. whether observing cillian murphy’s walk through a deserted london, his indoctrination into a makeshift family on a search for other survivors, or their treatment at the hands of an isolated army unit that quickly devolves into lord of the fliest territory… the film is just suffocating with its terror. it’s not an experience defined by jump scares, but by a permeation of details… every facet of every frame is an expression of a world that’s fucked beyond repair in the most horrifying conceivable way - like the best of zombie films it’s a twisted amplification of our status quo, but it’s a vision so complete in its terror that it packs a bite like none other.

66.) IN THE BEDROOM (dir. Todd Field)

i’m glad todd field recognized that he was a great director, because i never would have pegged Eyes Wide Shut’s Mr. Nightingale as much of anything, let alone the filmmaker perhaps most capable of solemnly piercing the deceptively placid meniscus of American domesticity… which both of Field’s features have done with an honest grace eons removed from the melodramatic wringers of Alan Ball and his ilk. In the Bedroom - his assured and eerily composed debut - eases its way into an ostensibly happy blue-collar maine community before obliterating it at the seams when a local boy is murdered by his older girlfriend’s ex-husband. carried by a string of astounding performances from the likes of tom wilkinson and sissy spacek and assured enough in its penetrating depictions to move along at an unfussy rhythm, In the Bedroom slowly (though punctuated by huge, plate-smashing spikes) erodes the foundations of modern living to reveal something primordial underneath… the last shot… a man long since surrendered to his animal impulses slowly sinking into his marriage bed, is just an insanely perfect moment.

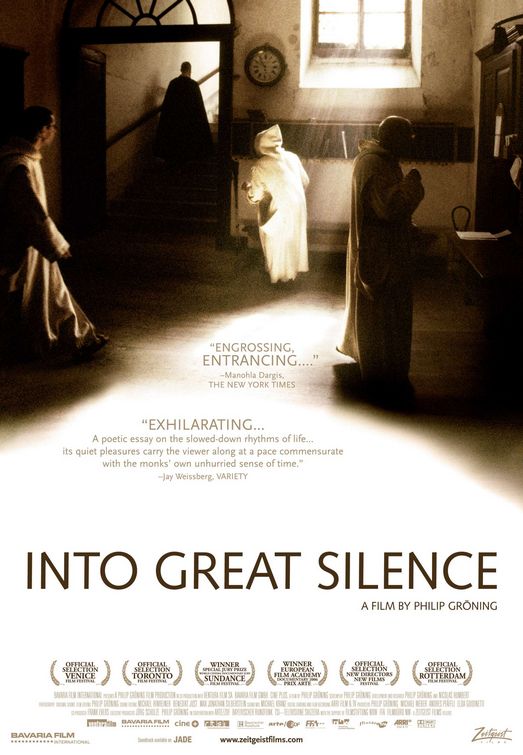

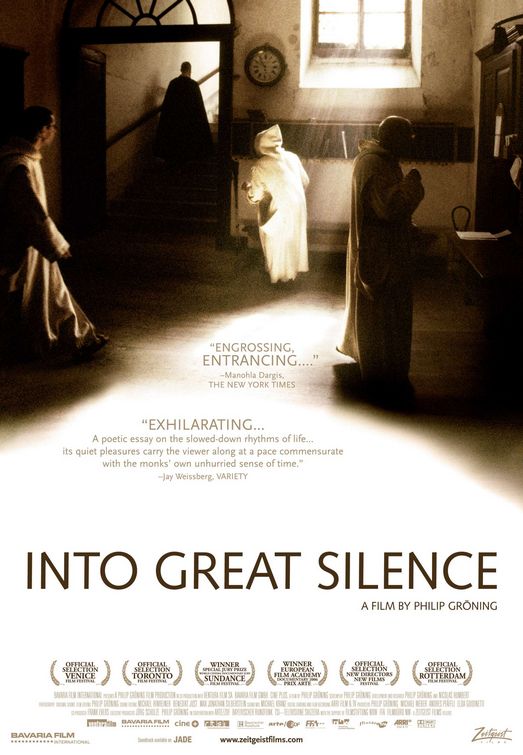

65.) INTO GREAT SILENCE (dir. Philip Groning)

after years of begging, philip groning was finally granted access to be the first filmmaker allowed to shoot at a Carthusian monastery high in the French Alps. he whittled the hundreds of hours of footage with which he returned into this stunning 2 1/2 document of a world the cinema has never known before… told as organically as possible, with gentle cuts, few words, a static camera, and little non-diagetic sound… Groning distills the daily rituals of this unique and secluded community to their essence, blissfully less concerned with the spirituality at work than the work itself… his patient and pleasant film is cinema of the senses at its most harmonious…these peaceful lives carried out in slow-motion where acts of menial labor - repeated endlessly - are revealed as synechdoches for entire existences.

64.) UP / RATATOUILLE (dir. Pete Docter / Brad Bird)

okay, so this one is actually a flagrant cheat… i just couldn’t choose between the two best films pixar has ever made. and if the imminent Cars 2 is any indication, the two best films pixar well ever make. Up gets a little bit too involved in its comic relief and Ratatouille has a bizarre concern with stealing that interrupts the lovely plot at all the wrong places, but for the most part, these two films are CG animation at its most vital. Up leans heavily upon the world of hayao miyazaki (if you’re gonna pay tribute to one filmmaker’s imagination, you can’t really do any better), but tells its simple story with such sweet purity that not even the tossed off ending can really impinge upon the desire to revisit this film… right about now. the details might be a bit slippery, but the fundamental beats of the story are so right… particularly in the first 45 minutes, every bit of information is so perfectly teased out with the time-tested aplomb of the best fables we’ve got.

Ratatouille is a hell of a lot more complex, but brad bird has never been interested in simple stories. in becoming one of the best storytellers we’ve got (medium be damned), he’s crafted pixar’s most complex and loaded narrative and wrapped it in a breathlessly kinetic bundle (the scene in which Remy first scurries into the restaurant’s kitchen is just superb action cinema). patton oswalt was an inspired choice as remy’s voice… and everything is just firing on all cylinders here to the point where the patently ridiculous love story is made all the more winning because of its fantastic execution… few films have ever been so perfectly clever. and - for what it’s worth - this is the only pixar film this side of Toy Story 2 to end on just the right note.

63.) NOBODY KNOWS (dir. Hirokazu Kore-eda)

look, hirokazu kore-eda is one of the world’s ten greatest working filmmakers. i haven’t yet succumbed to the compulsion to make that list, but… i mean, come on. it’s totally ridiculous that Nobody Knows - one of the crowning masterpieces of recent japanese cinema - is his third best film (his 1998 film After Life would prooobbabbly have been #1 or 2 on this distressingly long countdown had it been released this decade). the unfortunately true story of a flighty mother who abandoned her young kids in their tokyo apartment, this impeccably told urban epic peers unflinchingly into crevices of contemporary society that lesser filmmakers would be quick to sensationalize. bolstered by some of the best child performances i’ve ever seen, this damning portrait of modern decay and the apathy it breeds is unrepentant and unforgettable… where the abstract question of “who cares about the goy?” is answered in the worst way.

62.) THE WHITE RIBBON (dir. Michael Haneke)

because even nazis had childhoods, right? it only takes a look at the director behind this austere look at the genesis of ideology and the means by which its made hereditary to understand that its hyper-refined nature is a conduit to some seriously sinister stuff. the white ribbon is as pure a Michael Haneke film as they come… from the man who once said that he wants to “rape my viewers into autonomy,” the only surprise here is that this tale took him so long to tell. in the days leading up to WW1, something is afoul in an idyllic german village (filmed in crisp black and white as luscious as it is deeply ironic). a horse falls over a tripwire, sending its rider to the hospital. accidents abound. crops are destroyed. a building burns. blame is initially placed on an unsettling band of children, most of whom belong to one of cinema’s most obviously troubling fathers (a Protestant authoritarian who has warped the tenets of his faith into an unforgiving system of law). the local teacher falls in love. the seasons pass. a final shot as slyly enigmatic as any i can imagine. film moves with a leisurely yet harrowing inertia… a sublimated terror is systematically buried for over 140 minutes of insidiously elegant tension, until the film resolves not with a release, but with an uneasy resignation. as far as documenting evil in its infancy goes, this makes Rosemary’s Baby look like The Son of the Mask.

61.) THE DIVING BELL AND THE BUTTERFLY (dir. Julian Schnabel)

while i can personally attest to the widely accepted notion that julian schnabel is a raging asshole, he’s also a hell of a filmmaker. Schnabel has exclusively tackled the lives of artists in his film work, but in the remarkable circumstances of Jean-Baptiste Bauby he has finally found a vessel in which to channel the overwhelming formalism of Before Night Falls and Basquiat into something transcendent rather than self-serving. his tactics are bold and confining, but - with a tremendous assist from the great DP Janusz Kaminski - never reductive… the protracted stroke-victim POV shot with which the film begins, for example, actually plays upon its grandstanding nature. the viewer accepts its gimmicky feel and waits patiently for normative film language to take over. 7 or 8 minutes later and it starts to get a bit uncomfortable. by the time we’re treated to a medium shot of bauby’s hospital room, the relief is palpable, the ensuing story perfectly framed, and the viewer perched in a state of uncommon bodily awareness. schnabel wisely refuses to rest on his speedily earned laurels, and the film stretches into much more than a poignant technical exercise… but i’m tired and have to go to the rangers game now. you’ve seen this movie anyway, right?

0 comments:

Post a Comment